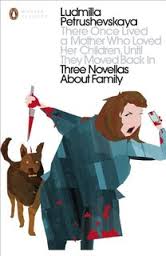

August is, once again, Women in Translation month, an opportunity to highlight some great women writers but also acknowledge the particular difficulties faced by women in being translated into English. While the gender barriers facing women writers who write in English have diminished (though inequality often remains as to how their work is perceived once in print), an unreasonably low percentage of literature translated into English (and that’s already an unreasonably low percentage of what is published) is by women. If you’re looking for a piece of literature which demonstrates the difficulties faced by women writers, however, you would be hard-pressed to beat Ludmilla Petrushevskaya’s novella ‘The Time is Night’ which is the centre piece of her newest collection from Penguin Classics, There Once Lived a Mother Who Loved Her Children, Until They Moved Back In.

The narrator of The Time is Night, Anna, is a poet who spends most of her time surviving poverty and her troublesome family rather than writing. The pram in the hall for her is the grandson, Tima, abandoned to her care, but, as she tells him, she remains somehow responsible for her mother and two children as well:

“But I must work, my little one – your Anna needs to provide for you, and for Granny Sima; Alena at least is using your child support and doesn’t bleed me for more. But Andrey, my beloved son, what about him? I must give him something, mustn’t I? For his injured foot (more on that later), for his life ruined in prison.”

To say ‘the story is narrated by’ doesn’t convey the experience of the reader: Anna’s narrative reads like an inner monologue, sometimes addressed to Tima, at other times simply to herself, moving back in time to recall the misfortunes’ of her family (Alena’s pregnancies and Andrey’s prison sentence) as well as detailing the difficulties of the present. While her own resilience is in evidence, there is plenty of vitriol to go with the love she feels for her children:

“Breaking into sobs, my daughter enumerated the sums she lived on, as if to say that we, Tima and I, were living in luxury while she was homeless. A home for her, I told her calmly, should come from the dick that knocked her up and then skipped off because no-one can stand her two days in a row.”

Men receive particularly short shrift: abusive, drunken, and with a tendency to disappear when needed. Anna nicknames Alena’s husband ‘the dud’:

“For god’s sake, my darling girl, kick him out! We’ll manage! What do we need him for? To stuff his face with our food? So you could humiliate yourself night after night begging his forgiveness?”

If this sounds rather desperate (it is) and bleak (it is), I can also say that it is riveting. Partly this is a kind of jaw-dropping astonishment at the pile up of horror upon horror, but it is also the vitality of the voice (credit to the translator Anna Summers) even in its moments of hate and anger. Strangely, it’s not without humour, for example when Anna reads her daughter’s diary with her own bracketed asides. The final section, where Anna attempts to prevent her mother being moved hospital and bring her home, becomes a kind of grotesque comedy.

‘The Time is Night’ is accompanied by two short stories, ‘Chocolates with Liqueur’ and ‘Among Friends’ (they’re described as novellas but neither is long enough). The first tells the story of a failed relationship (Petrushevskaya seems to allow no other kind). As in all three stories, living space is at a premium, and who is registered to live where is of enormous importance. In the story’s first chapter, the husband, Nikita, returns every night at seven to spend two hours in ‘his’ room. The second chapter returns to the beginning of their relationship, Nikita’s courtship, and the marriage which follows:

“Nikita needed a slave who would cost him nothing and whom he could kick whenever he wanted.”

The story is apparently a tribute to Edgar Allan Poe and ends in suitably gothic fashion.

The final story tells of a group of friends who meet every Friday for many years, their relationships slowly deteriorating. Initially it seems as dispiriting as everything that has gone before, but ultimately it is about a dying mother’s desire to safeguard her son – though in such a way as to suggest little faith in humanity.

I loved the stories in this volume: through their cynicism and despair some desperate but irrepressible life force still shines; it’s that force which continued to write.

Tags: ludmilla petrushevskaya, there once lived a mother who loved her children until they moved back in, WITMonth

August 3, 2015 at 8:14 pm |

Love the sound of this. I’m making a note of it for later.

August 5, 2015 at 2:59 pm |

Glad to hear it – a very strong voice, worth exploring.

August 3, 2015 at 8:37 pm |

Interesting Grant heard her name before but not read her

August 5, 2015 at 2:57 pm |

I think you would like her – hope you get a chance to give her a try.

August 4, 2015 at 6:40 am |

Great review, Grant. I’m hoping to hear about some new-to-me writers this month and Petrushevskaya certainly fits the bill. These stories sound full of energy.

August 5, 2015 at 2:58 pm |

As there seem to be a few people reading her this month you should get a fully rounded view. Hopefully you’ll decide to take the plunge!

August 4, 2015 at 7:14 am |

I saw this title and was fascinated – and your review and quotes remind me a little of the forthright comments and wry outlook on life of a Russian friend of mine… I’ll have to find it, thanks for the tip.

August 5, 2015 at 3:01 pm |

The introduction suggests that her work originates in oral story-telling, so you may well be on to something with your friend. (I also loved the title).

August 4, 2015 at 7:25 am |

What a great collection to start with Grant! I read her There Once Was a Girl Who Seduced Her Sister’s Husband, and He Hanged Himself in 2013 and was equally riveted by the voice, despite the propensity of the stories to revolve around dsyfunctional and fatalistic love. Great to see another collection available.

August 5, 2015 at 3:03 pm |

I’m glad to hear you found that similarly memorable. Given the stories told, you expect the voice to be little more than a whimper and yet it refuses to let go of life.

August 4, 2015 at 8:03 pm |

Great to see another collection from Petrushevskaya for #WITMonth … I’ve also kicked off with There Once Was a Girl Who Seduced Her Sister’s Husband, and He Hanged Himself her so called ‘Love Stories’ … feeling similar to you & Clare -desperate, dysfunctional, bleak- yet undoubtedly riveting! Will definitely seek out this collection too.

August 5, 2015 at 3:04 pm |

As will I be doing with her ‘love’ stories – it will certainly be interesting to see her take on that emotion!

August 6, 2015 at 2:29 pm |

This sounds rather horribly funny. The title alone (not to mention the previous one poppy mentions above) is terrific – like one of those Daniel Handler “Series of Unfortunate Events” books but for adult women.

August 9, 2015 at 8:53 pm |

‘Horribly funny’ sums it up, but with a very human core of resilience. I must admit I was immediately sold by the title!

July 24, 2023 at 5:40 pm |

[…] has three collections of her stories published by PMC, all with equally grotesque titles. There Once Lived a Mother Who Loved Her Children, Until They Moved Back In (translated by Anna Summers) has the advantage of containing probably her most famous work, the […]