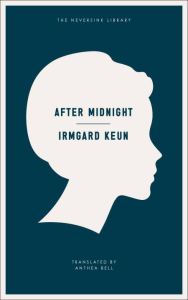

Though Irmgard Keun lived until 1982 – long enough to be appreciated as a writer for the second time – her best work is generally regarded to be those novels which describe living in Germany during the thirties: Gilgi (1931), The Artificial Silk Girl (1932) and After Midnight (1937) (alongside her exploration of exile, Child of All Nations, which was published in 1938). By After Midnight, the subjugation of all aspects of German life to National Socialism was impossible to ignore and it impresses itself on every page of the novel. Like Hans Fallada, however, Keun is interested in demonstrating the ways in which this new totalitarianism impacts on the life of ordinary men and women, particularly women.

The novel’s narrator is Susanne, or Sanna, a young woman who has already had to leave Cologne after being reported to the Gestapo by her relative, Aunt Adelheid, with whom she was staying at the time (an attempt to warn her off a developing relationship with her cousin, Franz), and now lives with her brother, Algin, and his wife, Liska, in Frankfurt. Algin is a once-successful writer who is threatened by the new regime:

“He has had another letter from the Reich Chamber of Literature. There’s going to be another purge of writers, and Algin will probably get eliminated. He might yet save himself by writing a long poem about the Fuhrer, something he has been most reluctant to do so far.”

It’s reasonable to assume Algin’s problems were also Keun’s, who was reluctant to go into exile, and later returned to Germany for the duration of the war. Keun, however, focuses the novel on the trials of the more prosaic Sanna and her friend Gerti. The novel takes place over one night, with flashbacks filling in the characters’ backgrounds, hence the title – though one can assume it also reflects a feeling that Germany has passed into a long, dark night of the soul. Sanna’s state of mind at the beginning is typical of many of the characters:

“I feel tired. Today was so eventful, such a strain. Life generally is these days. I don’t want to do anymore thinking. In fact, I can’t do anymore thinking. My brain’s all full of spots of light and darkness, circling in confusion.”

At present she is particularly concerned that Gerti will say the wrong thing – “Gerti ought not to go provoking an SA man like that” – as well as worrying about her friend’s relationship with Dieter:

“Dieter is what they call a person of mixed race, first class or maybe third class – I can never get the hang of these labels. But anyway, Gerti’s not supposed to have anything to do with him because of the race laws.”

Sanna’s confusion over ‘class’, and the informal nature of her language (’anyway’ features a lot in her vocabulary) actually highlights the ridiculousness of the prohibition. Her position as narrator, what might be termed her ‘common sense’ viewpoint, interested in individuals rather than politics, provides an effective vehicle for criticism. Anti-Semitism runs through every conversation, from Heini claiming that Breslauer, a Jewish doctor, is luckier than most (“I need my sympathy for thousands of fellow poverty-stricken emigrants”) to the claim of one visitor to the pub that he has discovered a way of divining Jews:

“You see, one can’t always tell who Jews are, straight off… But I can find him out with my rod!”

That he divulges this to Breslauer, bonded by their shared star sign, makes clear Keun’s view.

More generally, Politics is used as a weapon in petty rivalries and squabbles, as it was against Sanna by her Aunt. Franz also suffers when he attempts to set up a tobacconist’s shop with a friend to provide an income for himself and Sanna. Accused by a rival of anti-Nazi comments, by the time he is released the shop has been ransacked.

Though the pervading atmosphere of the novel is an almost unbearable tension, this is punctuated by two scenes of sudden violence which punch through any sense that life is somehow ‘carrying on’. Keun selects a day on which Hitler visits Frankfurt and we meet, among the celebrants, the young girl, Berta, who had been chosen to give him a bouquet and recite a poem. Hitler’s haste having rendered her surplus to requirements, she is performing for the benefit of the assembled drinkers when she collapses. “Bedtime for you!” her mother cries, but the girl is dead. The very unlikeliness of her death borders on comic, but this death foreshadows a later one which will provide the novel with its climax.

After Midnight is a heart-stopping evocation of Nazi Germany. Its narrow focus, both in terms of time and character, provide a snapshot of the everyday tensions, indignities and compromises faced by ordinary people whose loves and jealousies are immediately recognisable. The optimism of its ending seems slight in comparison.

Tags: after midnight, irmgard keun

November 10, 2017 at 7:40 am |

Having finally joined the Keun party with The Artificial Silk Girl, I’m definitely open to reading more of her work in the future. The more I read about this book the darker it sounds, but I guess that’s inevitable given the period and setting. Interesting to see the comparison with Hans Fallada in your opening comments – Alone in Berlin has been languishing on my shelves for ages, so maybe I need to read that first. Great review as ever, Grant – very thoughtful.

November 10, 2017 at 10:15 pm |

Thanks. Ironically, The Artificial Silk Girl is the one I haven’t read, but I’m sure I will. I’d definitely recommend Alone in Berlin – it has that similar feel of the view from the ground.

November 11, 2017 at 6:34 pm

I’m also quite curious to read Keun’s Gilgi at some point, partly because I suspect there might be some parallels with Silk Girl. Plus it seems a little easier to source than After Midnight!

November 12, 2017 at 6:11 pm

Yes, After Midnight was one of those books where I had to keep checking for an affordable copy!

November 10, 2017 at 10:39 am |

Great review, Grant. This was the first Keun book I read and I think it may well be my favourite of hers. “Heart-stopping” is the right phrase – such a powerful book.

November 10, 2017 at 10:17 pm |

Having read three of her novels I’m not sure I could pick a favourite though there was a lot to like about this – much more than I have covered. I certainly feel it succeeds in placing the reader in Germany at that point in history so strongly you can almost smell it!

November 10, 2017 at 4:56 pm |

Great review of a great book…

November 10, 2017 at 10:18 pm |

Thanks – I’ve really enjoyed getting to know Keun’s work – a pity there’s so little of it.

November 10, 2017 at 8:40 pm |

A writer I have yet to try

November 10, 2017 at 10:19 pm |

Hopefully at some point, Stu – I’m sure you would take to her.

November 11, 2017 at 12:33 pm |

Just commented on Jacqui’s post – I’ve never tried Keun’s work, but definitely one for the (near) future 🙂

November 12, 2017 at 6:11 pm |

You should, of course, read something which hasn’t been translated for the benefit of the rest of us!

November 12, 2017 at 11:30 pm

Grant – That’s an idea… 😉

December 5, 2017 at 10:02 am |

[…] Investigations of a Dog 1 Kehlmann: You Should Have Left 1 Keller: Stories 1 Keun: After Midnight 1 The Artificial Silk Girl 1 Kleist: An Earthquake in Chile 1 Kracht: Imperium – A Fiction of […]

June 6, 2021 at 11:21 am |

[…] a trio of novels – Gilgi, One of Us; The Artificial Silk Girl; and After Midnight – Irmgard Keun gives us the inside story of 1930s Germany from the point of view of young women […]

July 24, 2023 at 5:40 pm |

[…] view. Her most famous novels are those she wrote in the 1930s- Gilgi, The Artificial Silk Girl and After Midnight – detailing the lives of young women as the Nazis came to power. Ferdinand, the Man with the […]